HMRI is all about community but gut health researcher Dr Emily Hoedt is investigating another type of community – what she calls “the community in our guts”!

HMRI is all about community but gut health researcher Dr Emily Hoedt is investigating another type of community – what she calls “the community in our guts”!

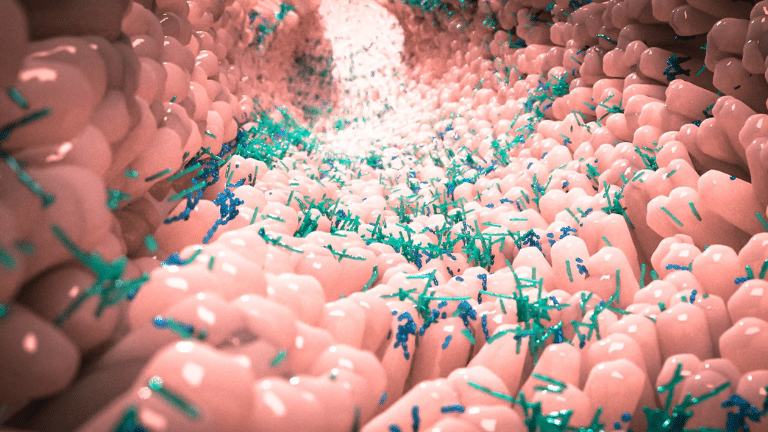

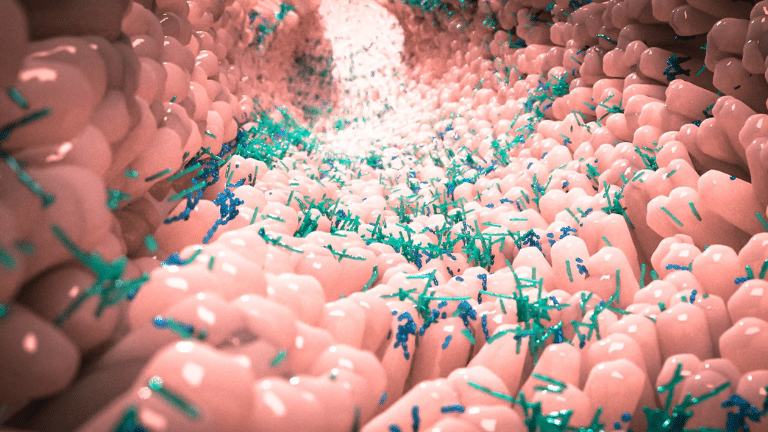

She is talking about the microbiome – the genes harboured by the estimated 10-100 trillion microbial cells in our bodies, primarily bacteria in the gut. And there may be a connection with bowel cancer.

Like all communities, the microbiome is made up of good and bad, of welcome and unwelcome members. And some are a mystery. Dr Hoedt explains, “About 20% of the microbiome is completely unknown. Because we don’t have a full grasp of this community in our guts, we can’t pinpoint what the bugs are responsible for. The microbiome is an unseen force that we are only just beginning to appreciate for the role it plays in our health.”

Dr Hoedt began her research career looking at the microbes responsible for methane production in kangaroos and cows! She completed her PhD at The University of Queensland and was most recently lead Postdoctoral Researcher on an academic-industry collaborative project conducted at APC Microbiome Ireland. Dr Hoedt is now attached to HMRI’s Immune Health Research Program and the Centre of Research Excellence in Digestive Health, where she oversees all aspects of microbiome research.

The work is important as gastrointestinal disease affects a large and growing percentage of the population. This is most likely due to diet because, of course, what we eat also feeds our microbes. The ultimate goal of Dr Hoedt’s research is to understand how we affect our gut microbiome – for better or worse – and how our microbiome in turn affects us.

Professor Simon Keely is a chief investigator of the HMRI Gastrointestinal Research Group and works closely with Dr Hoedt. He says, “Many people don’t appreciate just how widespread gastrointestinal diseases are in the community and how much they impact a person’s quality of life. A stigma is often attached to bowel disease, so it’s not talked about as much as other groups of disease. There is a great need for new research and new therapies for gastrointestinal diseases.”

Bowel cancer is the second most common type of newly diagnosed cancer in Australia and is Australia’s second-biggest cancer killer after lung cancer. Surgery for bowel cancer often includes anastomosis (bowel resectioning) where healthy sections of the bowel are joined after the unhealthy section has been removed. But local surgeons have identified an issue – in around 15% of patients the join is ineffective and if antibiotics can’t help, the results can be fatal. Anastomotic leak is the most severe complication of colorectal surgery. Its cause is unclear.

How does this relate to the microbiome? It is thought that the microbiome could be a driver for surgical leaks. Because of her microbiome expertise, Dr Hoedt was invited to join a project on bowel re-sectioning. She explains that her job is to look at what microbes might be responsible for adverse outcomes. This involves taking samples from the bowel of cancer patients before surgery and looking for specific signals.

“I love getting into the lab”, she says, “and trying to recover specific microbes, growing them and isolating them. We then use lab models to investigate if there’s inflammation. That’s how we find out which microbes are misbehaving.”

The microleaks project was co-founded by Dr Peter Pockney and Professor Keely with funding from the Cameron Family. As the lead clinician on the project, Dr Pockney coordinated sample collection and recruitment of the patients.

Dr Hoedt has presented the project, entitled “16S Sequencing of the Mucosal Associated Microbiota Reveals Taxa Associated with Anastomotic Leaks”, at multiple international conferences. A key finding from the team’s study of 159 patients was that there were significant differences in microbiota alpha diversity indices between ‘leak’ and ‘no leak’ patients.

The hope is that this research may open up avenues to manipulate the microbiota in order to reduce the risk of anastomotic leaks. This important research will soon be shared via publications and further conference presentations and the team will apply for further funding in order to extend the study to more patients, and trial some treatment interventions to reduce the chance of a surgical leak.

Dr Hoedt’s work promises improved comfort, dignity and health for bowel cancer patients.

HMRI would like to acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live, the Awabakal and Worimi peoples, and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We recognise and respect their cultural heritage and beliefs and their continued connection to their land.

Hunter Medical Research Institute

We’re taking healthy further.

Locked Bag 1000

New Lambton

NSW, Australia, 2305

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Copyright © 2024 Hunter Medical Research Institute | ABN: 27 081 436 919

Site by Marlin Communications