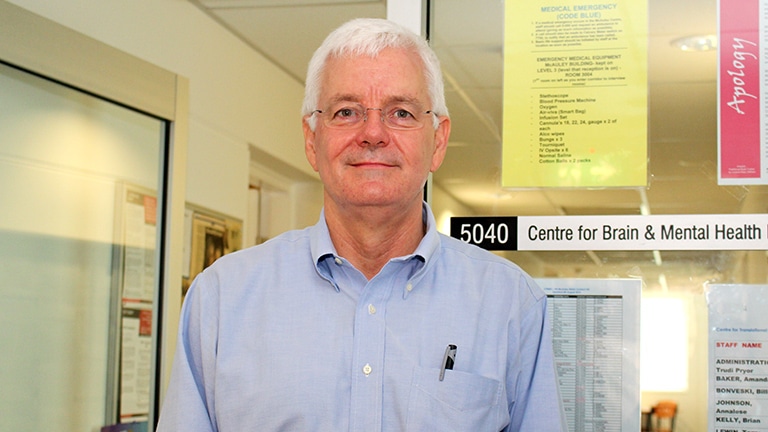

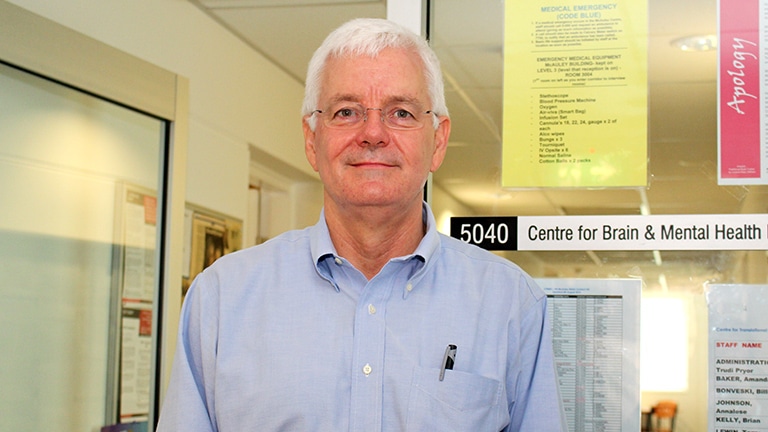

Professor Brian Kelly believes mental illness is not the sole domain of psychiatrists and psychologists but the responsibility of many in the health system.

Leading research is delivering a better response to depression when it is needed most.

Professor Brian Kelly believes mental illness is not the sole domain of psychiatrists and psychologists but the responsibility of many in the health system.

“Some of the most critical moments for improving the wellbeing of people who need mental health care occur in their day-to-day contact with frontline health professionals,” the University of Newcastle Professor of Psychiatry says.

“As mental health experts we need to be working more closely with those people to help them be confident and capable in responding to those day-to-day needs.”

Empowering people to respond appropriately when they sense that a patient is in emotional distress is a common thread in Kelly’s research. As a practising clinician and program convenor in the University’s Priority Research Centre (PRC) for Brain and Mental Health Research, he has a keen interest in seeing research translated into clinical practice.

An internationally-respected mental health authority who is consistently one of the University’s highest recipients of external research grants, Kelly has held a career-long interest in the psychosocial aspects of palliative care, particularly within an oncology setting.

He says it is often nurses and allied health-care providers in regular contact with patients who are in the best position initially to detect when a patient needs help.

Kelly advocates that mental health should be monitored as a ‘vital sign’ in people with cancer and other serious illnesses, assessed in the same way as a patient’s physical symptoms such as pain, pulse and blood pressure.

“This focus is rooted in very interesting and rewarding training I had as an undergraduate medical student at Newcastle,” Kelly explains.

“It was a strong philosophy of the medical school here that the behavioural, psychological, social and physical aspects of a patient’s condition were all linked and this thinking has flowed on to my clinical and research work today.

“It is a common misconception that when someone is suffering from depression and also has a severe illness, like advanced cancer, their mental health is beyond help.

“In fact, when people do receive this assistance they are often able to maintain a remarkable level of confidence and optimism, and are better equipped to deal with their illness.”

Kelly is collaborating with researchers in four other centres in Brisbane and Melbourne on the PROMPT study (Promoting Optimal Outcomes in Mood through Tailored Psychosocial Therapies). It provides training and mentorship to frontline health professionals, such as oncology nurses, to help them to confidently address common mental health problems among their patients.

“The challenge is to get these things into everyday practice and to see them embedded in people’s work,” Kelly says.

The project has parallels with research that Kelly completed as a former director of the University’s Centre for Rural and Remote Health in Orange, where he received significant NSW government funding develop a state-wide policy for emergency mental health care in rural areas. There, Kelly worked not only with frontline health workers such as GPs but other community members who could be the first point of contact for people with depression.

In many of those rural and farming communities the person they are most likely to speak to is not a health professional but the local stock and station agent or the bank manager, so we held forums where we got these people together and provided them with first aid training for mental health,” he says.

Kelly was hailed for the contributions he and his team made to government rural health policy and he continues to work in the field. He is currently a lead investigator on a five-year follow-up of the Australian Rural Mental Health Study, funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council.

“What I enjoy about my work in the PRC is that we have a tremendous team, with some very accomplished clinicians and researchers working across a broad range of fields,” he says.

“As well as in my own fields, we have achieved international acknowledgement in areas such as schizophrenia and drug and alcohol research. There is a genuine collegial atmosphere and willingness to work together that makes this centre quite unique.”

Professor Brian Kelly researches in collaboration with the Hunter Medical Research Institute’s (HMRI) Brain and Mental Health Program. HMRI is a partnership between the University of Newcastle, Hunter New England Local Health District and the community.

HMRI would like to acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live, the Awabakal and Worimi peoples, and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We recognise and respect their cultural heritage and beliefs and their continued connection to their land.

Hunter Medical Research Institute

We’re taking healthy further.

Locked Bag 1000

New Lambton

NSW, Australia, 2305

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Copyright © 2024 Hunter Medical Research Institute | ABN: 27 081 436 919

Site by Marlin Communications