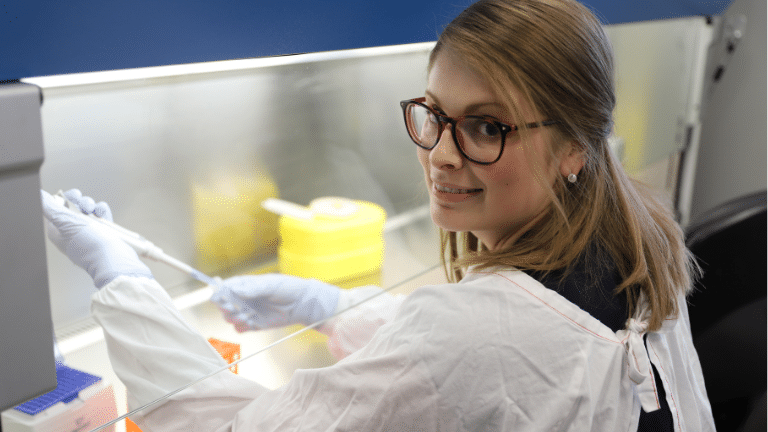

Gut health researcher Dr Grace Burns, from HMRI’s Immune Health Research Program, says that the term IBS has been around for decades for but it’s only in the past 15 years or so that the medical community has started to take it seriously.

Gut health researcher Dr Grace Burns, from HMRI’s Immune Health Research Program, says that the term IBS has been around for decades, but it’s only in the past 15 years or so that the medical community has started to take it seriously.

“Previously it was seen as a psychosomatic condition because you can’t see any bleeding or obvious inflammation on an endoscopy or colonoscopy,” says Grace.

“While there’s no visible inflammation, we now know that there’s micro-inflammation and there are changes in the microbiota,” she says.

The term IBS describes a range of conditions that relate to defecation patterns. There’s 3 main types – IBS D (for diarrhoea), IBS C (for constipation), IBS M (for mixed diarrhoea and constipation) – and a diagnosis usually involves chronic ongoing symptoms for six months or more.

The triggers are believed to range from psychological and physiological stress, diet and infections like gastroenteritis, water borne diseases, contaminated water and possibly even COVID-19.

“IBS is a real black box of ‘I don’t know’. We treat the symptoms without understanding the underlying cause,” says Grace.

While not life-threatening, IBS can be a day-to-day battle for some people. It causes pain, fatigue and also sometimes anxiety, depression and insomnia in addition to the significant impacts on productivity and daily activity.

“I know that many people find it very validating and affirming to get a diagnosis of IBS. Lots of people have struggled in silence for years, avoiding certain activities and making sure they’re always close to a bathroom. There was a global survey a few years back that found that nearly 40% of people had some sort of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, with 3.5% of these respondents from Australia meeting the diagnostic criteria for IBS,” says Grace.

HMRI researchers are currently investigating the relationship between the gut and circadian-related pathways, specifically melatonin and serotonin, as well as immune signatures and dietary and microbial patterns that might contribute to chronic symptom burden. Dysfunction in the gut could potentially lead to insomnia and anxiety symptoms.

“There’s so much that is only just being discovered about the microbiome-gut-brain axis. By understanding the mechanisms that drive IBS, we hope that researchers will contribute to changes in IBS management that improve quality of life of those living with IBS” says Grace.

For more information about these studies and how you can participate, visit the Centre of Research Excellence in Digestive Health here

HMRI would like to acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the land on which we work and live, the Awabakal and Worimi peoples, and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We recognise and respect their cultural heritage and beliefs and their continued connection to their land.

Hunter Medical Research Institute

We’re taking healthy further.

Locked Bag 1000

New Lambton

NSW, Australia, 2305

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Copyright © 2024 Hunter Medical Research Institute | ABN: 27 081 436 919

Site by Marlin Communications