Every health check you’ve ever had was once an idea in a scientist’s mind. From blood and biopsies, to scans and saliva swabs, researchers are constantly working on better, faster ways to detect disease and diagnose problems.

So what does the future of health checks look like?

Using cell junk to diagnose disease

University of Newcastle researcher Professor Murray Cairns from HMRI’s Precision Medicine research program is focusing on two key areas when it comes to health checks.

He is exploring how extracellular vesicles (EVs) – once considered cell junk of no diagnostic value – can be used to detect disease.

Murray says, “Every cell in your body releases EVs. They break away and circulate in the tissue, blood and lymph. They are very useful because they are fully encapsulated – they have a lipid membrane that means that the molecules inside are protected.

“They carry a little sample of the cells that came from. For example, if they come from the kidneys they have nephrons in them, if they come from the brain, they have neurons in them. This means you can identify EVs from tissue types.

“I am very interested in brain EV’s because you can’t biopsy live brain tissue. We can target specific EVs in the lab. We use an antibody to target transmembrane ligands (molecules that stick out of the EV) so we can isolate synaptic EVs and test them.

“This is useful for diagnosing brain and psychiatric disoders but some people are looking at EVs generally,” says Murray.

Sequencing your genome to predict risk

The information in an Ancestry.com or 23andMee genetic test is enough to analyse gene variants that will have the most impact on your health.

Murray says that for around $100, we could all potentially have a genetic test that would identify our major inherited disease risks.

“It’s cheap, you only have to have it done once in your life and it’s good for identifying hundreds of syndromes and drugs that will work for you,” he says.

While genetic testing is used widely in oncology, it’s more expensive because you have to dig deeper.

With genomic testing, you can identify with 100% accuracy someone’s risk of developing certain diseases (i.e. Fragile X syndrome, muscular dystrophy), but it can also do a very good job of predicting risk of common diseases that can be modified through lifestyle changes such as diet and exercise.

“This kind of testing tells you the risk but not the diagnosis. For example, if you have a genetic predisposition to high cholesterol which is a key factor in heart disease, you could start taking statins before it’s too late,” says Murray.

Lung cancer breathalyser

University of Newcastle and HMRI Cancer Detection and Therapies researchers, Dr Renee Goreham and PhD student Emma Morris have created an early-stage breathalyser prototype that can detect EVs.

The EVs in a person’s breath carry biomarkers. By capturing and testing the breath, it can be tested for the specific biomarkers associated with lung cancer.

In time, the researchers hope to develop a breathalyser similar to the ones used to test for alcohol. It would be a portable, easy-to-use, ergonomically friendly device that would be used for lung cancer screening.

The hope is that by screening before symptoms appear, lung cancer will be caught in the early stages when it’s still very treatable. Read more about this here.

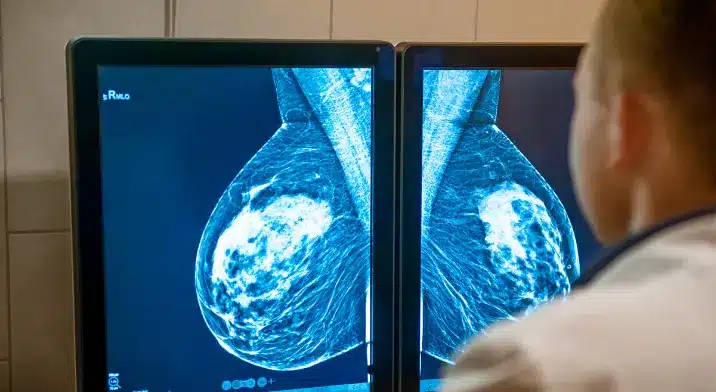

Painless scans to detect tumours

Dr Renee Goreham, Associate Professor John Holdsworth and PhD candidate Catherine Merx are also working on a ‘squishless’ breast cancer imaging technique that uses infrared light.

Renee says, “Think of it like using a flashlight to see through your hand, but much more advanced. This technique could make breast cancer screening more comfortable, accessible and encourage more women to get checked.” You can read more about it here.

University of Newcastle and HMRI Brain Neuromodulation research program PhD candidate Christian Behler, in partnership with Dr Bryan Paton from the HMRI Imaging Centre, is in the early stages of exploring thermography for tumour detection in brain tissue.

Tumours in the brain have a different temperature signature due to their vascular structure and the variability of blood supply (they show up as cooler or hotter than other parts of the brain). The brain is very sensitive to temperature.

The idea is to monitor brain temperature in order to identify and locate tumours, and then use nanoparticles loaded with iron to infiltrate the tumour tissue.

The MRI then interacts with the iron in the tumour tissue, effectively microwaving it and killing it.

This is an alternative to excision and an option for when the tumours are inoperable (e.g DIPG). This research is in the very early stages but it’s a promising concept.

Health checks to do now

New health checks and screenings are always becoming available. Most people are familiar with Rapid Antigen Tests (RATs) which can test for common respiratory viruses, but before the COVID-19 pandemic, most of us had never heard of them.

Likewise, one of the most recent additions to the healthcare landscape is the self-exam cervical screening kit that provides a less confronting way to be checked for cervical cancer.

Whether it’s blood, tissue, breath or finding new uses for scanning technology, HMRI’s researchers are exploring new ways to detect cancer, schizophrenia, hypertension, Parkinson’s Disease and more.

If you want to know which health screening tests and checks are recommended for your age and gender, you can ask your GP or a trusted health professional.