Hunter Medical Research Institute’s Cancer Detection and Therapy Research Program is developing new approaches to help transform cancer treatments and improve the lives of people with cancer.

Cancer research has led to significant improvements in the prevention, early detection, and treatment of cancer. While some types of cancer can be cured, for others there are few effective treatments.

Our team is working to find ways to detect cancer earlier with the goal of developing cures or treatments that save lives.

Around 1 in 50 Australians currently live with cancer, with skin cancer being the most common type.

165,000

AUSTRALIANS WERE NEWLY DIAGNOSED WITH CANCER IN 2023

3 in 10

DEATHS IN AUSTRALIA ARE FROM CANCER

20% INCREASE

IN CANCER SURVIVAL RATES OVER THE LAST 25 YEARS

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

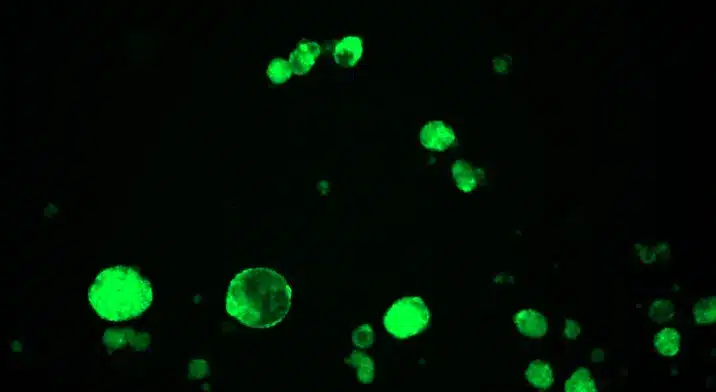

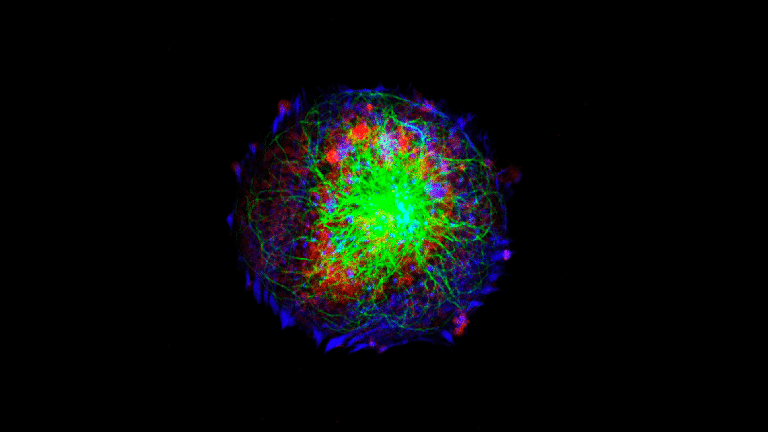

Nearly all cancer deaths occur because the cancer becomes resistant to treatment and spreads to other organs and parts of the body, a process called metastasis.

The causes of cancer, the triggers of metastasis, recurrence and treatment resistance remain largely unknown.

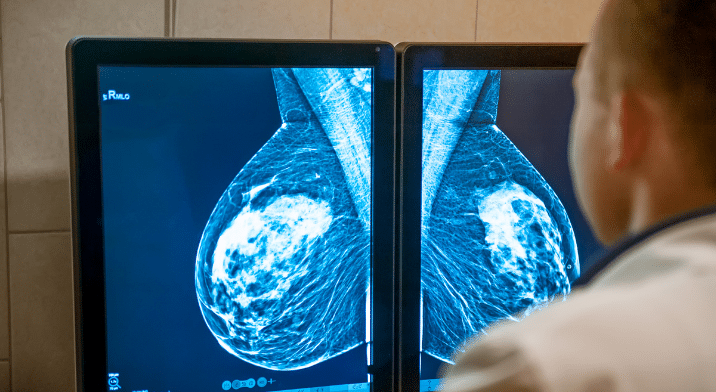

Our researchers are focusing on developing treatments that effectively target cancer that has spread to secondary sites. We are also working to identify novel biomarkers that effectively track or predict disease onset or progression.

This program aims to rapidly translate discoveries into clinical practice to transform the health and wellbeing of people with cancer.

Our close partnership with NSW Health Pathology helps combine expertise, allowing us to continually optimise and translate our discoveries into pathology practice.

This will improve the lives of millions of patients around the world.

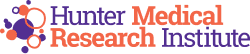

Bringing together leading expertise in the fight against cancer

Our Cancer Detection and Therapy Research Program brings together related research groups carrying out different aspects of cancer research.

The research program works across a range of cancers with particular expertise in:

- Cancer genetics

- Isoform biology

- Radiation physics

- Neuro-oncology

- Gynaecological-oncology

- Molecular mechanisms

- Liquid biopsy analysis

- Drug discovery and drug delivery

Our wide range of expertise enables us to employ varied and complex methodologies. This depth allows us to provide unique insights into disease development and progression.